Wide-column design

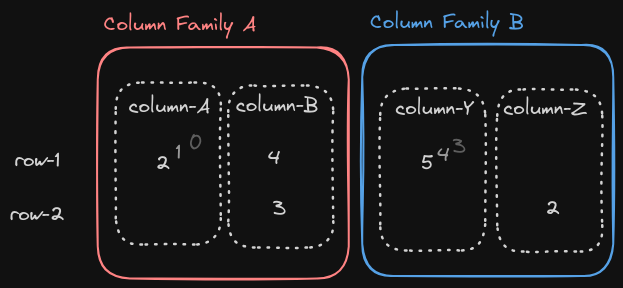

Like Bigtable, Smoltable is a wide-column [1] database. It could be described as a sparse, persistent multi-dimensional sorted map. Every table is sorted by the row key, which is a unique identifier for each row. There are no secondary indexes. This may seem limiting but surprisingly many access patterns can be modelled this way.

The row key is not necessarily the same as the primary key in a relational database: A row in general is not a fixed structure like in a relational database. Each row may contain arbitrarily many columns, grouped into column families. Column families must be defined upfront, but column qualifiers (column names) can be defined dynamically, and do not need to adhere to a fixed schema. Because the table is sparse, unused columns do not cost any disk space. Retrieving specific columns does not require retrieving the entire row.

Each row’s cells are sorted by the column key (family + qualifier), and a timestamp: this results in a multi-dimensional key:

row key + col family + col qualifier + ts

which maps to some value, the cell value. The cell value, unlike in Bigtable, can be a certain type:

- string (UTF-8 encoded string)

- boolean (like Byte, but is unmarshalled as boolean)

- byte (unsigned integer, 1 byte)

- i32 (signed integer, 4 bytes)

- i64 (signed integer, 8 bytes)

- f32 (floating point, 4 bytes)

- f64 (floating point, 8 bytes)

The timestamp allows storing multiple versions of the same cell.

Columns as data

Consider this scenario: We want to store a fleet of aircrafts, each having a list of flights and some metadata. One possible naive implementation would be:

| row key | value: |

|---|---|

| plane#TF-FIR#flight#FI318 | 2024-01-25 |

| plane#TF-FIR#flight#FI319 | 2024-01-25 |

| plane#TF-FIR#meta#miles | 51000000 |

| plane#TF-FIR#meta#model | Boeing 757-256 |

| plane#TF-FIR#meta#operator | Icelandair |

| plane#D-AIQN#flight#EW7033 | 2019-10-31 |

| plane#D-AIQN#flight#EW7036 | 2019-10-31 |

| plane#D-AIQN#meta#miles | 52142142 |

| plane#D-AIQN#meta#model | Airbus A320-211 |

| plane#D-AIQN#meta#operator | Germanwings |

For every attribute, a composite row key is used, and maps to a very generic value: column family, using

the empty column as column qualifier. To get flights, a prefix scan over plane#TF-FIR#flight# could be used.

To get metadata, plane#TF-FIR#meta#.

Naturally, this is an awkward, suboptimal schema. If you find yourself working exclusively with row keys and an vertically growing table, take a step back for some minutes and try to refactor your schema.

As one plane is a single entity, that should ideally be the row key. We can use column families and columns to restructure our data:

| row key | flight:FI318 | flight:FI319 | flight:EW7033 | flight:EW7036 | meta:miles | meta:model | meta:operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plane#TF-FIR | 2024-01-25 | 2024-01-25 | 51000000 | Boeing 757-256 | Icelandair | ||

| plane#D-AIQN | 2019-10-31 | 2019-10-31 | 52142142 | Airbus A320-211 | Germanwings |

We can easily store all data in a single row, using two column families, flight and meta. Meta contains arbitrary columns

of different kind of metadata, while each column inside flights is a flight number, with the cell value being the flight data.

Remember, unused columns do not account into space usage. To retrieve data, we can a specific column and use a column filter.

Both layout use 10 cells, however the column-oriented one uses much simpler row keys, which need less disk space, are more readable and can be retrieved by row key instead of resorting to prefix queries.

Now, we have been tasked to extend flights to store their start and destination airport. We could keep the flight columns and store structured

data (e.g. JSON) into each cell, or refactor the table to store each flight as a separate row:

| row key | loc:start | loc:dest | meta:date | meta:miles | meta:model | meta:operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plane#TF-FIR | 51000000 | Boeing 757-256 | Icelandair | |||

| plane#D-AIQN | 52142142 | Airbus A320-211 | Germanwings | |||

| flight#TF-FIR#FI318 | KEF | OSL | 2024-01-25 | |||

| flight#TF-FIR#FI319 | OSL | KEF | 2024-01-25 | |||

| flight#D-AIQN#EW7033 | CGN | HAM | 2019-10-31 | |||

| flight#D-AIQN#EW7036 | HAM | CGN | 2019-10-31 |

Now, using a scan with prefix flight#TF-FIR# we can get all flights of TF-FIR.

Row key design

As mentioned before, there are no secondary indices and no query planner. The ordering of the table is defined by the row key, which in return will determine how efficient scans over specific rows and columns are.

When using multiple components in a row key, sorting them by cardinality generally optimizes locality and allows better querying. Compare:

<CONTINENT>#<COUNTRY>#<CITY> and <CITY>#<COUNTRY>#<CONTINENT>.

The second row key will always perform a full table scan if we search only for a specific continent or country, because we cannot use a prefix.

Customizing sorting behaviour

By using a multi-component date or a fixed-length integer, data can be sorted.

Using the above example, by adding a YYYY-MM-DD component to the row key, we can sort flights per plane in ascending order:

| row key | loc:start | loc:dest | meta:miles | meta:model | meta:operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plane#TF-FIR | 51000000 | Boeing 757-256 | Icelandair | ||

| plane#D-AIQN | 52142142 | Airbus A320-211 | Germanwings | ||

| flight#TF-FIR#2024-01-25#FI318 | KEF | OSL | |||

| flight#TF-FIR#2024-01-25#FI319 | OSL | KEF | |||

| flight#D-AIQN#2019-10-31#EW7033 | CGN | HAM | |||

| flight#D-AIQN#2019-10-31#EW7036 | HAM | CGN |

Now, using a scan with prefix flight#TF-FIR#2024-01- we can get all flights of TF-FIR in January 2024.

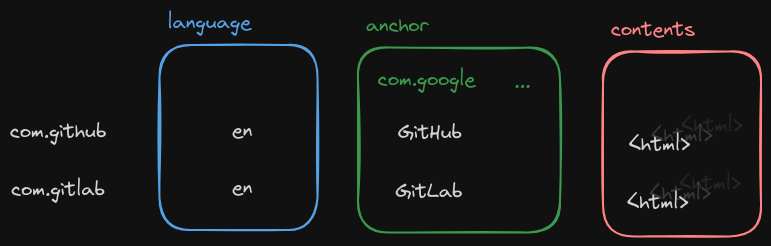

Real-life example: Webtable

The webtable, the heart of the Google search engine, is stored in Bigtable. It stores web pages and references (anchors) between said pages.

languagecontains a single column containing the language code (e.g. DE).anchorare links that point to the given website (backlinks), where each column qualifier is an anchor’s href attribute. The cell value is the anchor text (el.textContentin JavaScript).contentscontains a single column containing the raw HTML document. By moving it into a separate locality group the rather large documents will not slow down frequent queries accessing the other columns. By using cell versions, the table can store a history of the web page.

The row key is the reversed domain key. This maximizes locality of pages under the same (sub-)domain.

By listing the anchors of a row, we can count how many websites link to this specific page (for example to calculate the PageRank).

For simplicity the examples do not show full row keys. Domains alone are not enough to store the entire internet, so a real row key would also contain the pathname, like:

com.github/com.github/aboutcom.github/pricing

Summary

This is a summary based on parts of Bigtable’s documentation that apply to Smoltable. Read more here, but not everything applies to Smoltable.

Data schema

- Each table has only one index, the row key

- Rows are sorted lexicographically by row key

- Column families are stored in any specific order (this differs from Bigtable)

- Columns are grouped by column family and sorted in lexicographic order within the column family

Column families

- Put related columns in the same column family

- Choose short names for your column families

- Put columns that have different data retention needs in different column families

Columns

- Treat column qualifiers as data, if possible

- Give column qualifiers short but meaningful names

Rows

- Keep all information for an entity in a single row

- Design your row key based on the queries you will use to retrieve the data (see row key design)

- Store related entities in adjacent rows

- Store multiple delimited values in each row key

- Keep your row keys short

- Pad integers with leading zeroes: important for timestamps where range-based queries are used

- Do not use sequential numeric IDs as row key

[1] The origin of the term “wide-column” is not exactly easy to narrow down. It was mentioned in “Scalable SQL and NoSQL Data Stores” by Rick Cattell in 2010. If you know an earlier mention of the term, please let us now!